Strengthening Creative Placemaking: Designing Toward Equity

The Madisonville Community Studio is an ongoing project co-created by Madisonville residents and Design Impact (DI) to explore key questions about the inclusiveness of neighborhood changes. The project is supported by the Kresge Foundation.

For 10 years, Design Impact’s work has taught us that sustainable social change happens at the intersection of equity, creativity, and leadership (read more about our theory of change here). Each of our projects and partnerships represents this multidisciplinary approach. So when we talk about design and creativity in the context of creative placemaking, it always lives alongside leadership and equity practices. The Madisonville Community Studio project was no different.

However, we also knew that through the work of the Madisonville Community Studio we had the opportunity and obligation to deeply examine structural racism and how it shows in neighborhood development. To do this effectively, we knew it meant we had to make some changes to our typical approach.

At the heart of most of our projects is community-engaged design, a collaborative and creative process to solve problems. Communities or organizations can apply it to a challenge to define, explore, and solve problems. In community-engaged design, the people most affected by the problem are actively involved in co-designing solutions. Through this process, we strive to move beyond community feedback and into community leadership. The process itself begins by looking at the problem from many angles, deciding which opportunities for change to pursue, brainstorming potential solutions and developing small tests of those ideas to get buy-in and feedback.

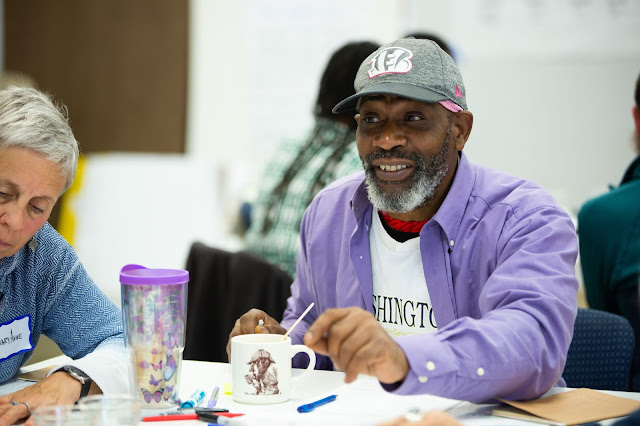

Studio participants at work on a Saturday, discussing in small groups opportunities to build deeper connections with residents in the neighborhood.

As we continue to work in Madisonville and in other communities facing similar challenges, these lessons and adaptations stick with us. As a learning organization, we know that we are always a work in progress and that new insights emerge for us everyday. We know that our commitment to community and to our mission requires that we listen, reflect, and do the vulnerable work of changing. As we deconstruct and reimagine new ways of working and being together, we invite you to share with us your stories, questions, and ideas.

Written by Sarah Corlett, Director of Community Development and Strategy

For 10 years, Design Impact’s work has taught us that sustainable social change happens at the intersection of equity, creativity, and leadership (read more about our theory of change here). Each of our projects and partnerships represents this multidisciplinary approach. So when we talk about design and creativity in the context of creative placemaking, it always lives alongside leadership and equity practices. The Madisonville Community Studio project was no different.

However, we also knew that through the work of the Madisonville Community Studio we had the opportunity and obligation to deeply examine structural racism and how it shows in neighborhood development. To do this effectively, we knew it meant we had to make some changes to our typical approach.

At the heart of most of our projects is community-engaged design, a collaborative and creative process to solve problems. Communities or organizations can apply it to a challenge to define, explore, and solve problems. In community-engaged design, the people most affected by the problem are actively involved in co-designing solutions. Through this process, we strive to move beyond community feedback and into community leadership. The process itself begins by looking at the problem from many angles, deciding which opportunities for change to pursue, brainstorming potential solutions and developing small tests of those ideas to get buy-in and feedback.

Studio participants at work on a Saturday, discussing in small groups opportunities to build deeper connections with residents in the neighborhood.

Over the last several years, DI has leaned into this community-engaged design approach as a creative placemaking strategy in Cincinnati and other communities around the country. Each neighborhood we worked with was looking for ways to develop more inclusively and needed a different process to do it. Looking back, many aspects of community-engaged design served these projects well such as collaboration with the community, the application of creativity to bring people together and generate new approaches, and the process’ orientation to action. But in preparation for the Madisonville design studio, we also reflected on how pieces of our work in these neighborhoods fell short. In particular, we noted that we tended to move too quickly, did not go beyond acknowledging racism, and did not move marginalized people into positions of power.

We took these learnings seriously and drastically changed our process and approach. The Madisonville community studio continues to be an opportunity to apply what we learned over the last decade and strengthen the roles of leadership and equity practices while still leaning heavily into what works best in community-engaged design. With the generous funding, patient timelines and trust from the Kresge Foundation, we have been able to incorporate these learnings into our work. We changed our process in three critical ways: we slowed down, designed racial equity into our whole process, and prioritized Black participants' perspectives.

Where we fell short in the past:

- We too moved quickly. While the action-orientation of community-engaged design is one of its strengths, it is not known for its ability to provide space for deep reflection and connection that can make or break long term results. In addition, we were often constrained by timelines, budget, and capacity, and funder’s drive towards action-which at times caused us to move too quickly and gloss over the deeper issues that needed to be addressed for sustainable social change to occur.

- We did not go beyond acknowledging racism. We did call explicit attention to racism's role in neighborhood development in the past and today. But we failed to connect this acknowledgment to what it means for individuals and organizations and how they need to show up differently to the work.

- We did not move marginalized people into positions of power. While the residents fully participated in the community-engaged process and were often implementers of new approaches, they were not always given a platform that continued to give them agency and power after the project's end.

We took these learnings seriously and drastically changed our process and approach. The Madisonville community studio continues to be an opportunity to apply what we learned over the last decade and strengthen the roles of leadership and equity practices while still leaning heavily into what works best in community-engaged design. With the generous funding, patient timelines and trust from the Kresge Foundation, we have been able to incorporate these learnings into our work. We changed our process in three critical ways: we slowed down, designed racial equity into our whole process, and prioritized Black participants' perspectives.

Slow down

Community-engaged design is celebrated for its ability to move teams toward action quickly. But unpacking structural racism demands us to slow down. It takes time to unpack the ways white supremacy shows up in our city, in our communities and within ourselves. We did not want to rush people or miss the opportunity for critical conversations for the sake of moving quickly. Often we threw out our agenda to make space for challenging conversations that drew us closer together.Design the racial equity lens into every interaction and step

In America, we avoid conversations about racism, especially in white or multiracial spaces. We found in our community studio that it took constant attention to direct people towards a practice of noticing where racism was manifesting within themselves, in relationships with individuals and in their neighborhood.“It’s too easy for white people to walk away. It’s not safe [to stay in the conversation]. The point of this is to be uncomfortable and face up to it. Where are we ignorant? Not owning up to what we get--all the things we’ve gotten. There is a price for that and [we need to] acknowledge it and pay it.”

- Madisonville Studio Participant

Prioritize the perspective of Black participants

We cannot assume that through the mere act of co-creation, people with more power and privilege will value the lived experiences of those who are oppressed or encourage them to share their power. We had to purposefully create an environment that consistently elevated Black residents’ voices to undo patterns that center the voices of white residents. In doing so, residents truly shared power. To learn more about how we created this type of space and tools we used, read “Healing as We Build.”As we continue to work in Madisonville and in other communities facing similar challenges, these lessons and adaptations stick with us. As a learning organization, we know that we are always a work in progress and that new insights emerge for us everyday. We know that our commitment to community and to our mission requires that we listen, reflect, and do the vulnerable work of changing. As we deconstruct and reimagine new ways of working and being together, we invite you to share with us your stories, questions, and ideas.

Written by Sarah Corlett, Director of Community Development and Strategy